In this paper, published in The Cryosphere, we used Raman spectroscopy to trace carbonaceous material from the shoreline to the furthest reaches of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf.

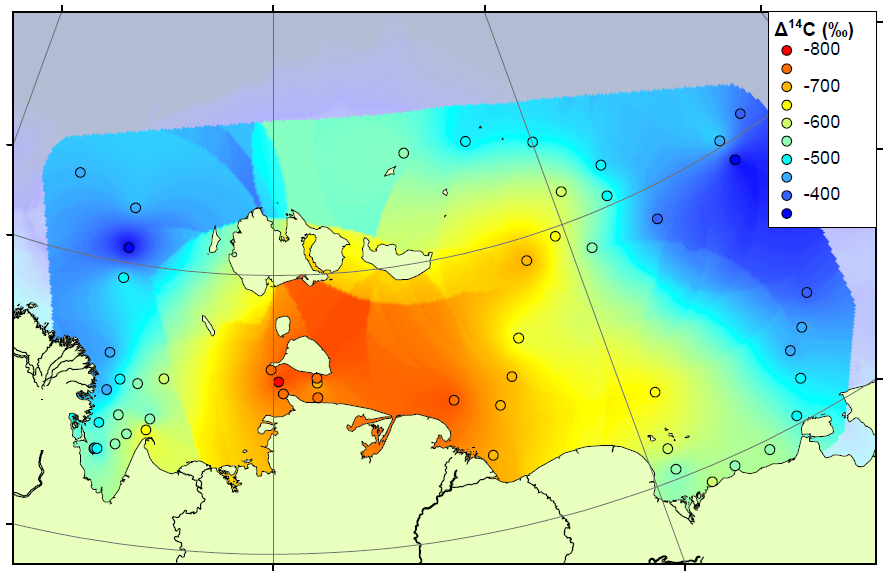

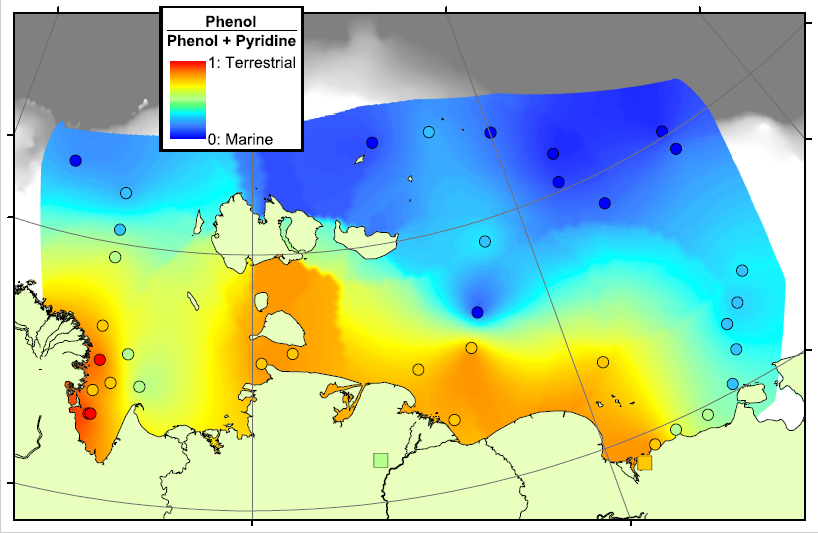

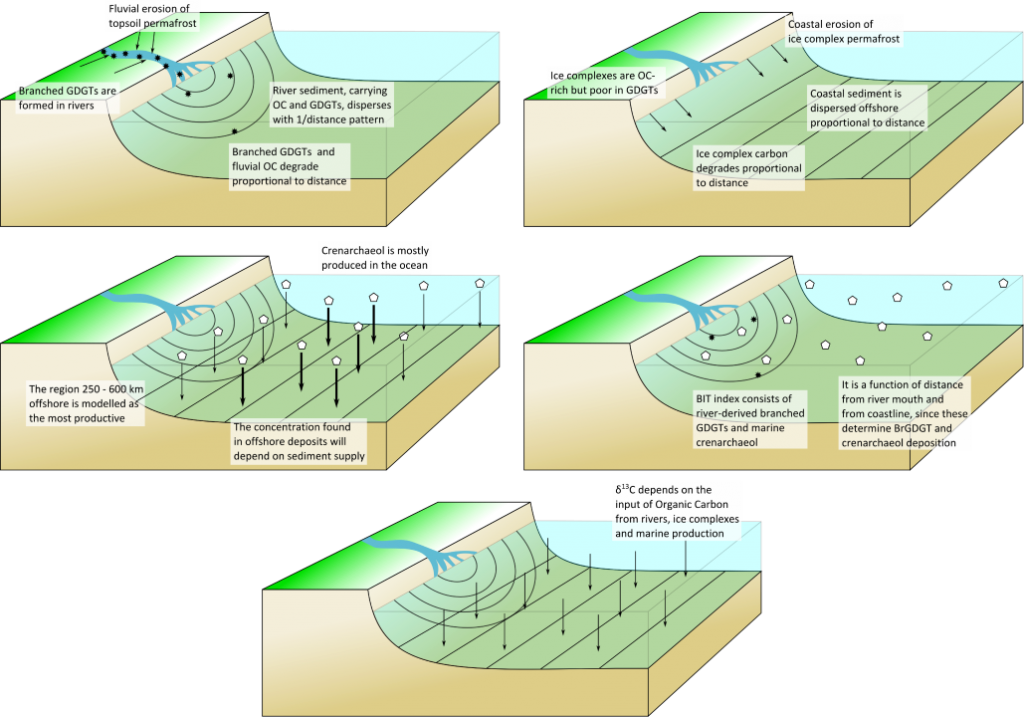

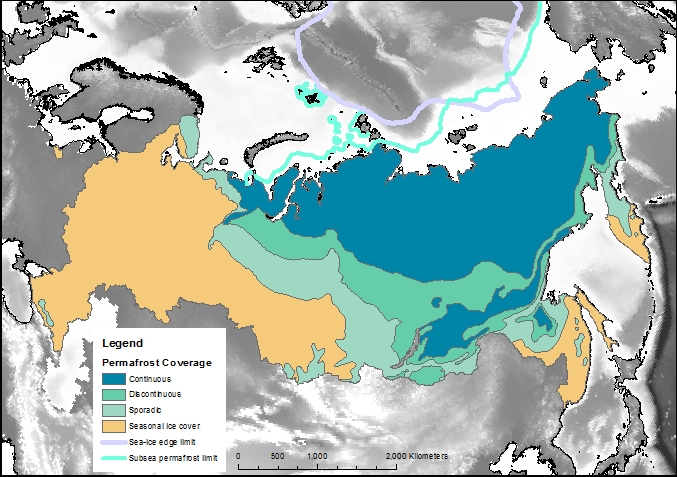

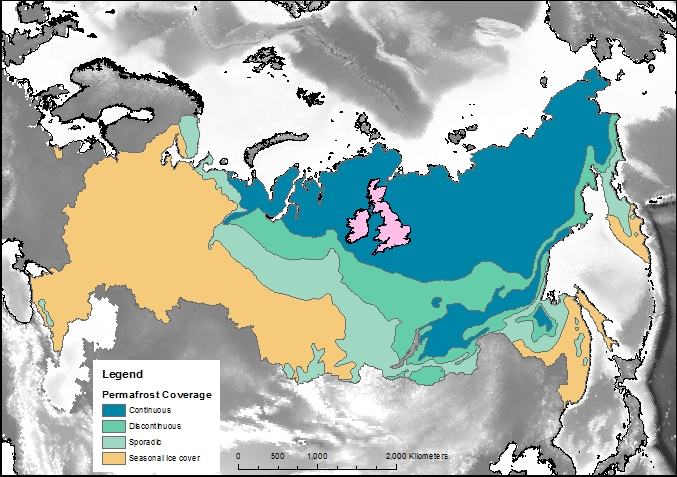

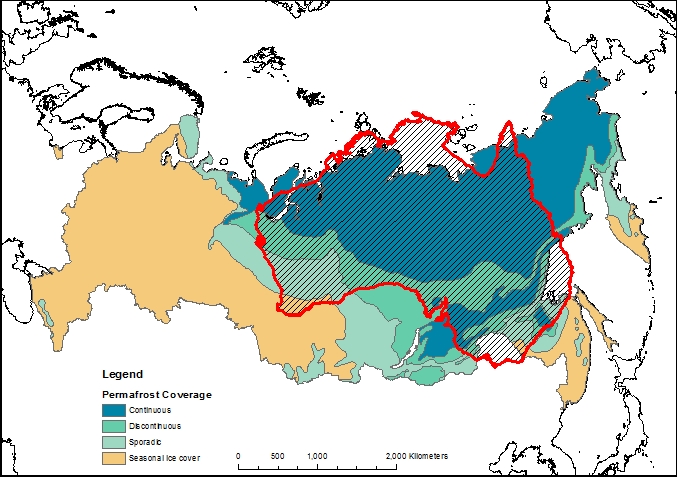

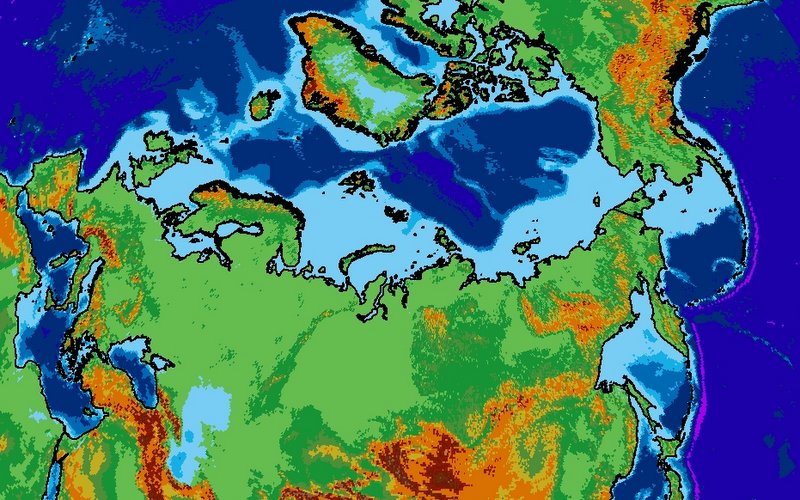

Raman spectroscopy uses laser light to determine the molecular structure of a wide range of materials. During my PhD, I showed that Raman could be used to probe individual particles of organic carbon to show whether they were disordered, like coal, or crystalline sheets of graphite. This collection of carbon particles, known as carbonaceous materials, are particularly hardwearing and resistant to breaking down during erosion and transport. During my post-doctoral research, I then used a range of organic geochemistry techniques to investigate the transition from terrestrial to marine carbon across the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, showing that coastal erosion and river erosion were both supplying organic matter to the ocean.

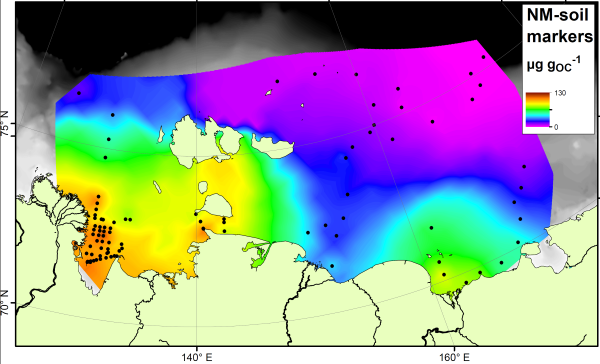

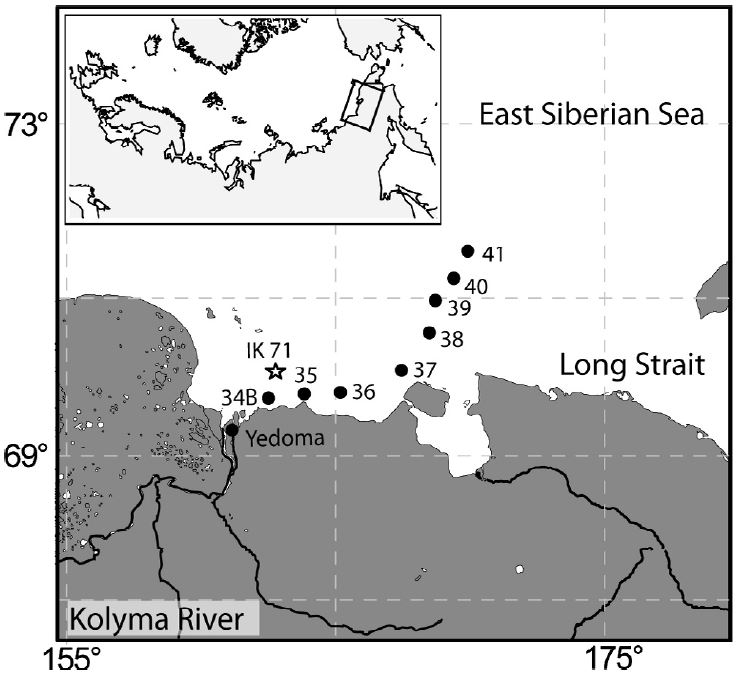

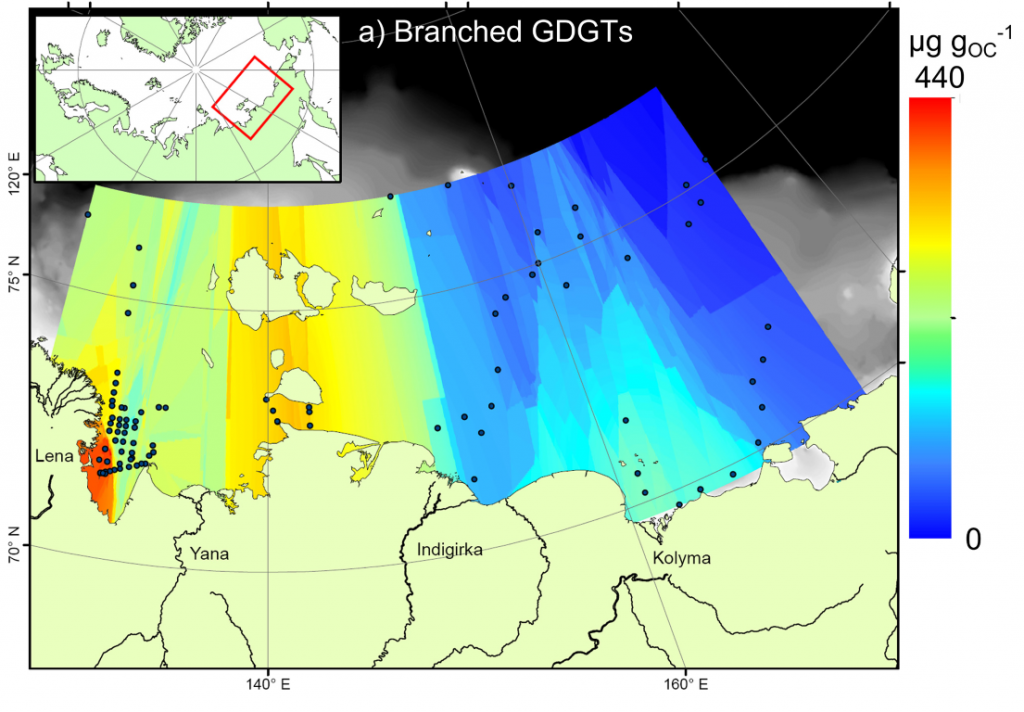

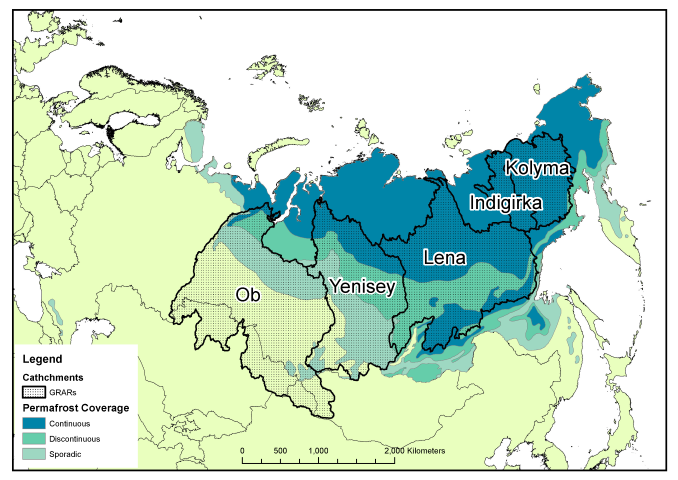

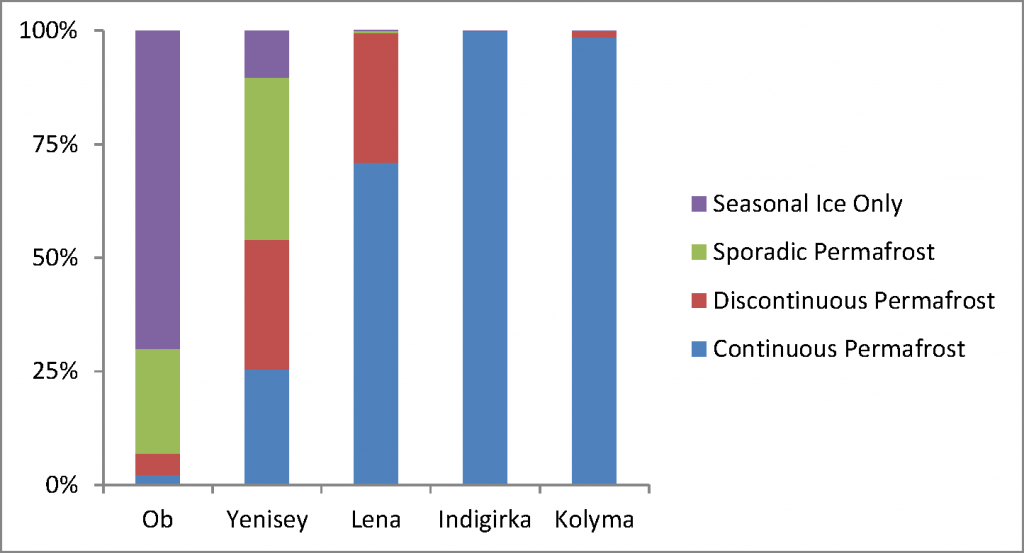

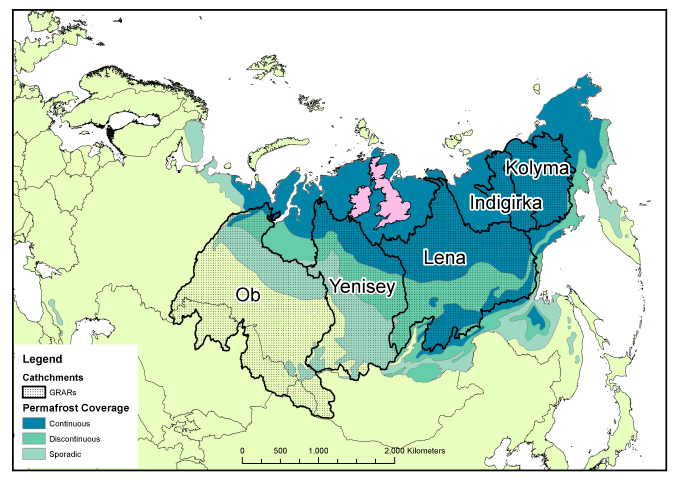

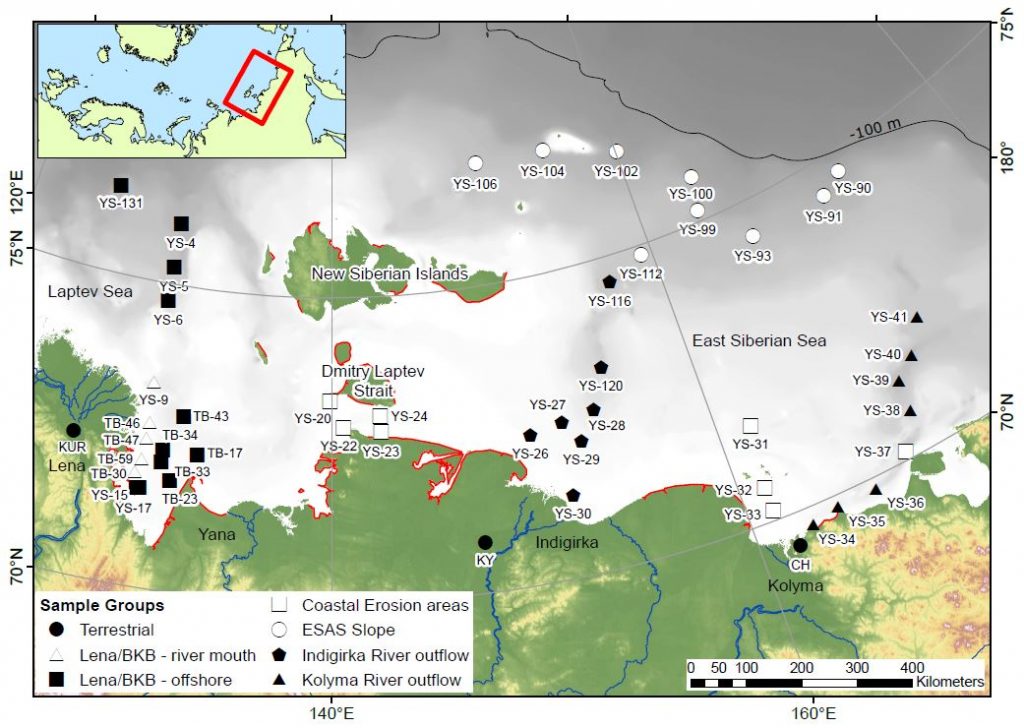

This study uses the Raman technique on those same Arctic Shelf sediments to look at the sources and distribution of carbonaceous material on the shelf. The samples used in our paper were collected from close to the mouths of some major rivers, from areas experiencing rapid coastal erosion, and from hundreds of kilometres offshore.

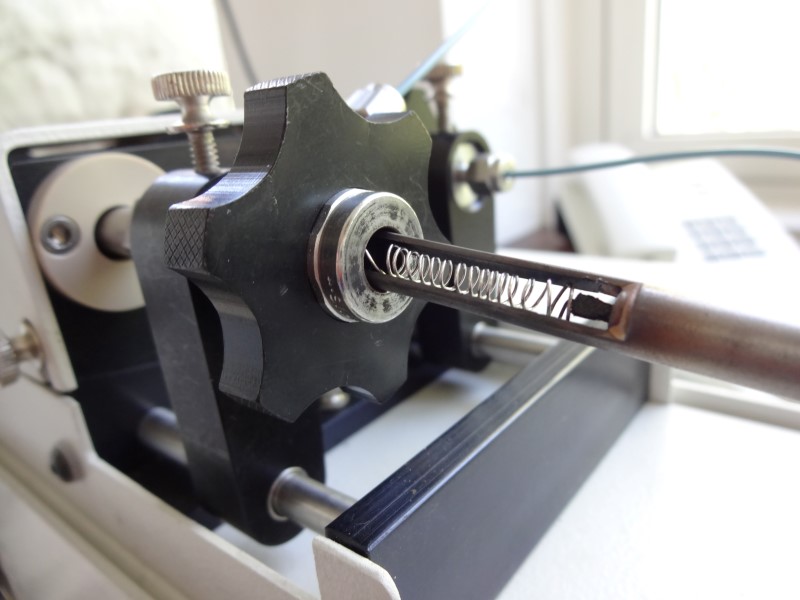

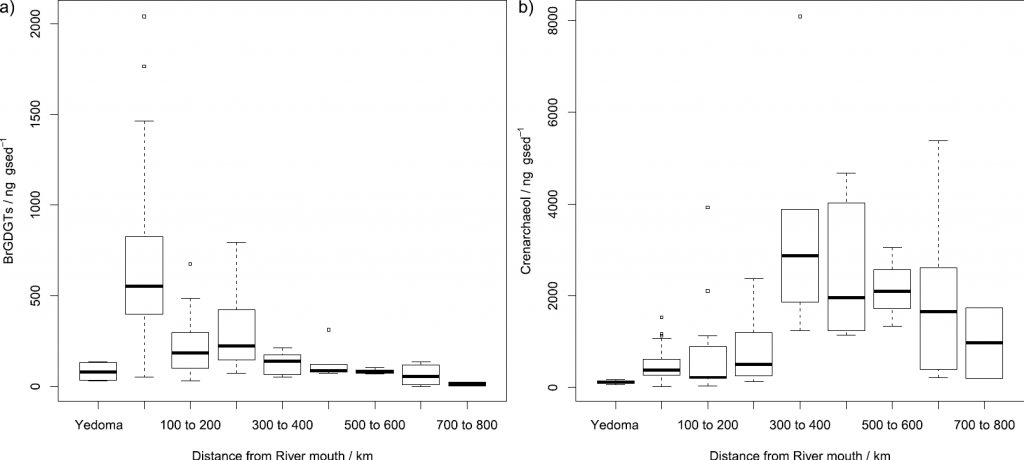

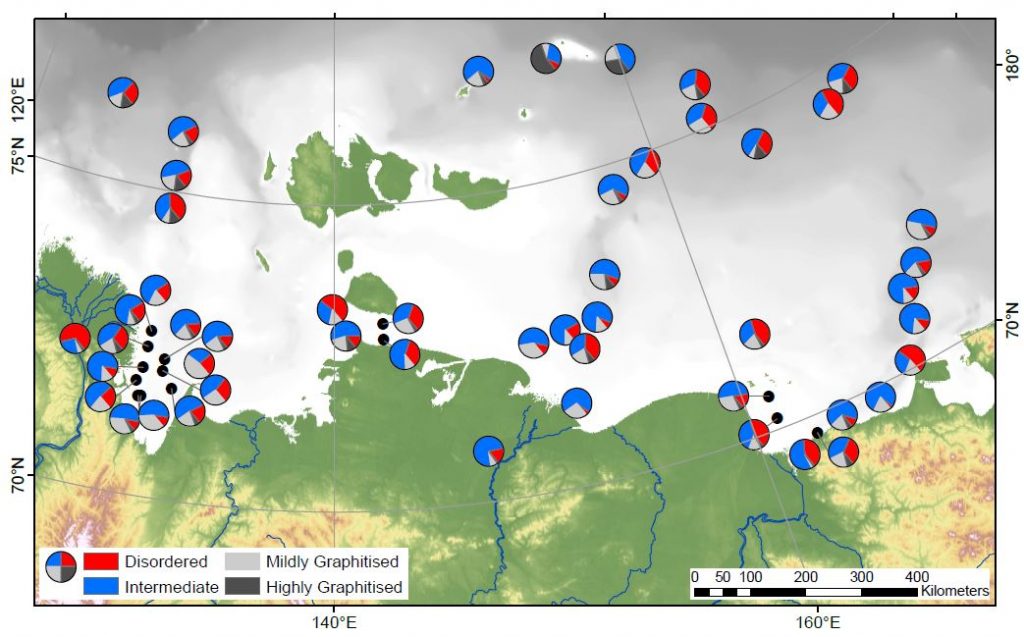

The hardest work, collecting over 1400 Raman spectra, was carried out by two undergraduate students, Melissa Maher and Jerome Blewett, who are co-authors on the paper. The collected spectra were then analysed using an automated peak fitting script, and grouped according to the shape of the fitted peaks. This provides an unbiased method for determining whether a carbon particle is highly graphitised, mildly graphitised, disordered, or somewhere in between. For each of the sites on the shelf we collected spectra from up to 30 particles, and looked at how many fitted into each group. Statistics were then used to spot patterns across the shelf.

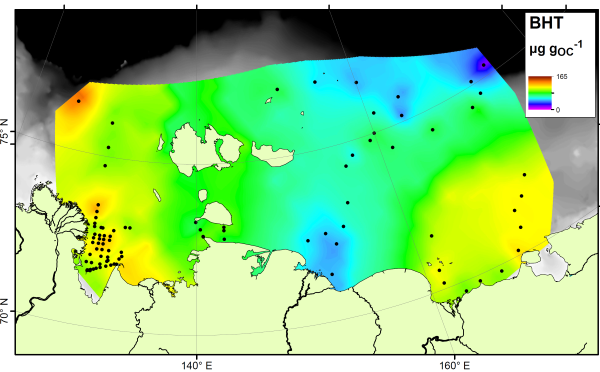

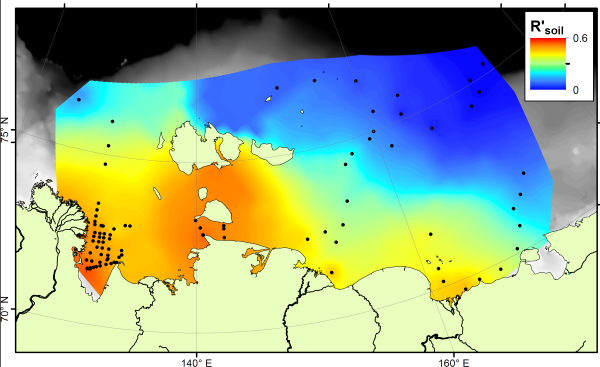

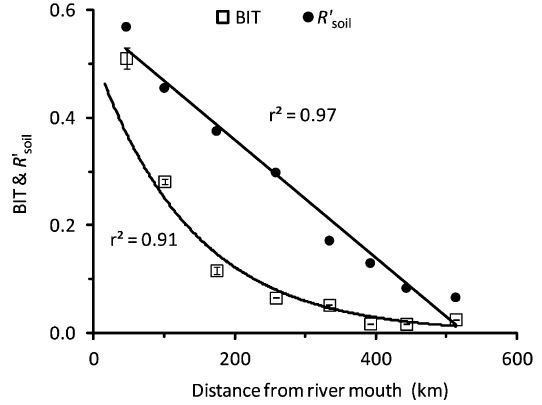

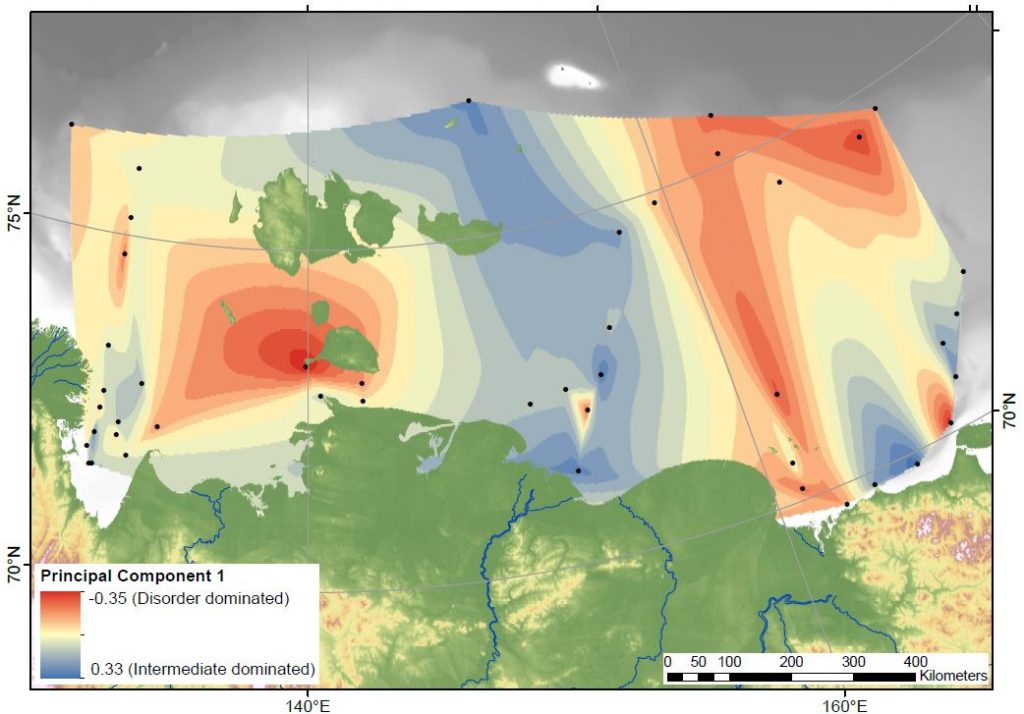

Our first finding is that the relative proportion of “disordered” and “intermediate” carbon particles varies, and that there are patches with more of one or the other group. At the coastline these patches align with two of the major rivers (Kolyma and Indigirka) and areas of rapid coastal erosion. Surprisingly, the patches can then be traced all the way across the shelf. We would have expected the currents in the ocean to have mixed the particles together further offshore, and in the biomarker studies we’ve done before we did not spot this kind of pattern. This means that Raman is a great way to trace the different sediment and carbon sources on the shelf.

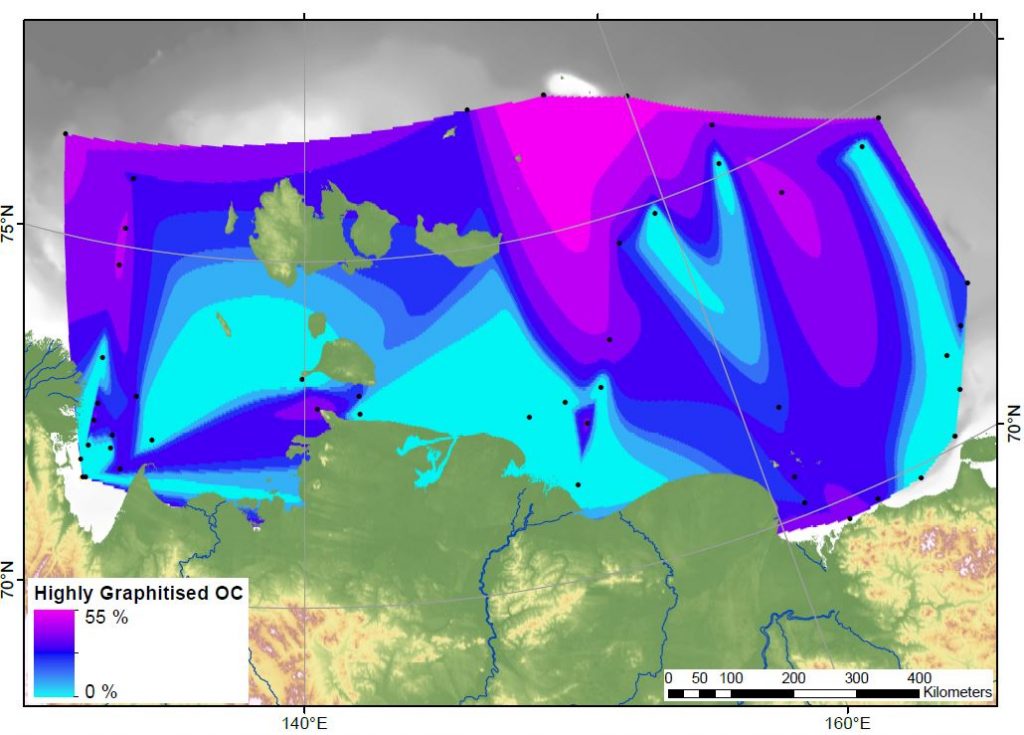

Our second finding is that the amount of “highly graphitised” carbon particles is highest in the furthest offshore samples. These very crystalline flakes of graphite are behaving differently to all the other carbon particle groups. It’s not clear exactly why this is, but one option is that everything else is breaking down and degrading before getting that far offshore. Or, the graphite particles could be so light that they sink very slowly, floating out to the shelf edge much easier than the other types.

This problem has implications for the global carbon cycle. These carbon particles have been released from permafrost on land and transported for hundreds of kilometres offshore, a trip that has taken thousands of years. If all of the carbonaceous material can survive the journey, it means that this fraction of the organic matter is not at risk of being degraded and released to the atmosphere as greenhouse gases. Burying it in the ocean provides protection from degradation for thousands or millions of years. Future studies should look at just how well the carbon particles can survive erosion and burial.

In summary, carbonaceous material is resilient to degradation and can be used to trace sediment sources across the Arctic shelf.

The Cryosphere, 12, 3293-3309, 2018

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3293-2018