06/09/2016 UPDATE: The paper has been accepted and is now published. The final version is available from the journal.

Our international team of East Siberian researchers currently has a paper in open review at Biogeosciences. The discussion paper, and its interactive comments, can be downloaded from the journal website.

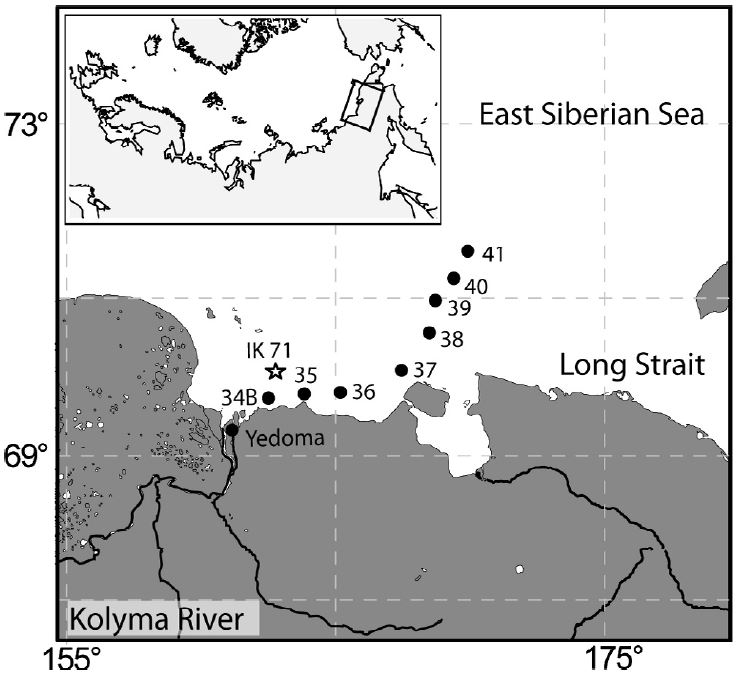

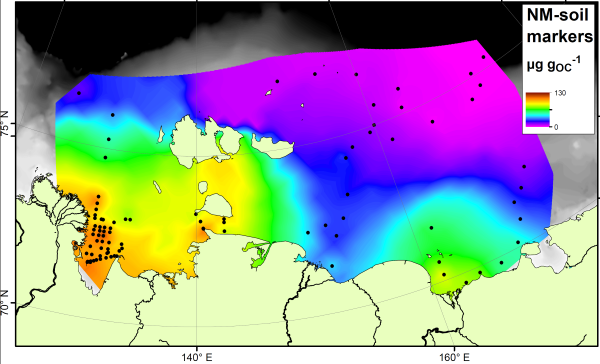

The paper studies a group of compounds called “bacteriohopanepolyols” (BHPs for short), which are found in the cell membranes of a range of microbes and are therefore one of the most common organic compounds around. They are found in modern and ancient sediments from all over the world. This study has concentrated on two groups of these. Group 1 is the soil marker compounds. These are only found in soils, and so have been used as tracers for soil material in rivers, lakes and offshore. Here is how they are spread across the East Siberian Artic Shelf:

Note how the soil marker concentrations are highest (orange colours) near to the rivers and coastlines. By measuring the concentration next to the river mouths, and in the sediments being washed away by coastal erosion, we show that it is not just rivers that are delivering the soil markers to the Arctic Ocean.

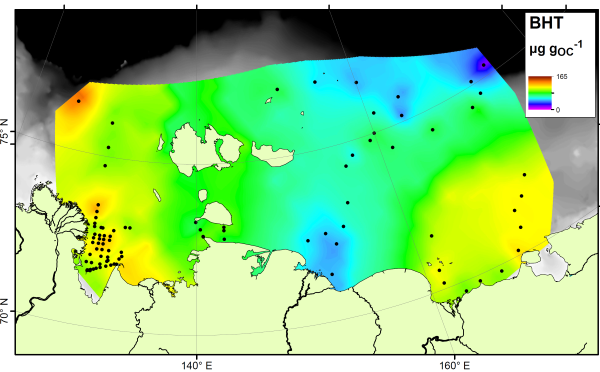

There is no single compound that is a true tracer for carbon produced in the ocean itself, but the compound bacteriohopanetetrol (BHT) is most abundant in marine settings despite being found in soils as well. Therefore if your sample is rich in BHT, and poor in soil markers, it is likely dominated by carbon from the ocean. Here’s a map of BHT across the East Siberian Arctic Shelf:

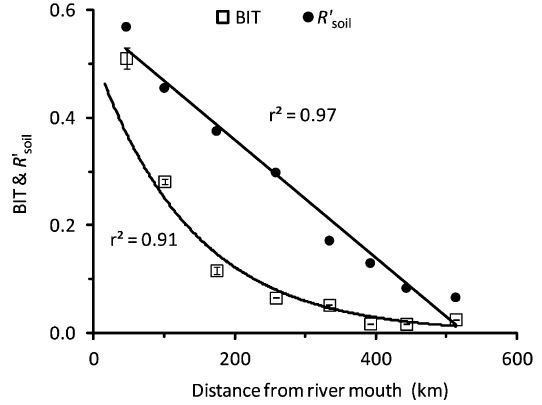

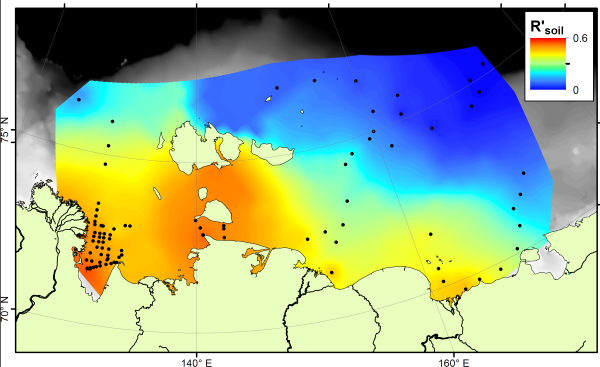

The BHT results show a fairly constant amount across the ocean floor. If we compare the soil marker concentrations to the BHT concentrations, we can see which areas are rich in soil carbon (more soil markers than BHT) and which are rich in marine carbon (more BHT than soil markers). This comparison is called the R’soil index, and is shown below:

The R’soil index shows that all along the East Siberian Arctic coastline, offshore sediments are dominated by carbon from the land. As you go further offshore, especially in eastern parts nearer to the Pacific Ocean, marine carbon is more important. This result shows a similar pattern to that seen using stable carbon isotopes, but is different to the pattern shown by the BIT index. Therefore these two indices, both based on microbial biomarkers, are tracing different parts of the carbon cycle.