This paper was published in the open access journal Earth Surface Dynamics, and is available through the journal website and the MMU e-space repository.

The paper is a combined effort from a large team of researchers interested in the way that organic carbon is exported from small tropical islands. These islands are very biologically productive, the forest grows quickly in the warm, wet climate. They are also responsible for delivering large amounts of sediment to the ocean. Rocks are weakened by earthquakes and then eroded by the frequent tropical storms that hit the islands. This washes sediment and carbon out to sea via two mechanisms. High sediment concentrations lead to ‘hyperpycnal’ plumes of material flowing along the ocean floor, lower sediment concentrations cause ‘hypopycnal’ flows that stay at the ocean surface. Both systems can spread sediments and carbon a long way offshore.

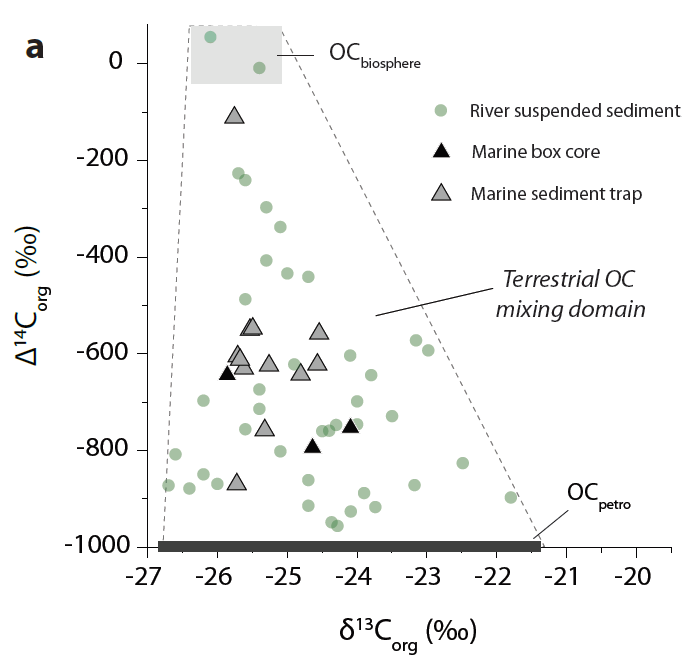

It had long been thought that hyperpycnal delivery of sediment, which usually only occurs in the most extreme weather conditions when floods deliver vast amounts of sediment to the ocean in a short period of time, were efficient methods of organic carbon preservation. Our data confirmed this hypothesis, showing that little terrestrial organic carbon was lost during transport, and little marine carbon added to the mixture.

However, the dataset also investigated how efficient hypopycnal delivery can be. Sediment and carbon are delivered throughout the year, in smaller floods and less extreme storms, and it had been suspected that this mechanism exposed the carbon to oxidising conditions where it could be degraded and released as CO2. We showed that in Taiwan, where hypopycnal conditions exist but are still receiving and accumulating a large amount of sediment, the burial efficiency of carbon in hypopycnal conditions is still very high. Marine carbon is mixed into the sediments, but at least 70% of the terrestrial carbon survives.

This means that small tropical islands are even better at exporting and burying carbon than was previously thought, and therefore better at sequestering atmospheric CO2. We estimated that more than 8 Teragrams (million tonnes) of carbon could be buried each year throughout Oceania.