Collection of the top 15 cm of sediment using a steel auger.

Author: Robert Sparkes

008 Preparing Elemental Analysis Foils

Adding sediment to tin foil cups prior to quantification of C, N, O, H or S via Elemental Analysis.

007 Furnacing Organic Matter

Removal of organic matter from sediments using a moderate-temperature furnace.

006 Acid Decarbonation

Removal of carbonate minerals (inorganic carbon) using hydrochloric acid.

Note: this process also removes some organic matter (publication in review).

005 Concentrated Acid Digestion

Extracting elements from sediments using concentrated nitric acid.

004 Glassware Cleaning

Washing and furnacing glassware to remove contamination.

003 Grinding and Sieving

Producing uniformly fine powdered sediment for further analysis.

001 Oven Drying of Sediments

Drying sediment to remove moisture prior to storage or analysis.

Rapid carbon accumulation at a saltmarshrestored by managed realignment exceeded carbon emitted in direct site construction

In the last few years, I have expanded my research into the burial of carbon in saltmarsh environments, especially around the UK. This is the first paper I have published on the topic. The paper is available Open Access via the journal website.

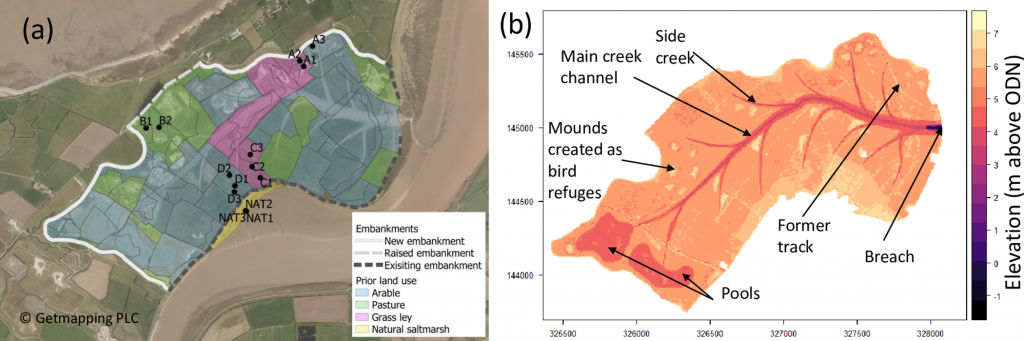

Saltmarshes, which is an coastal wetland which is flooded and drained by saltwater brought in on the high tide, are natural features acrosst the UK and around the world. In the UK, many saltmarshes were drained to form farmland, with a sea defence built between the drained marsh and the river or estuary. Rising sea levels threaten the reclaimed marshes, and the nearby fields, towns and villages, with flooding. Often it is decided that retreating from the drained land is the best way to protect other, more valuable, assets nearby. Through a process called “managed realignment”, the sea defences are breached and the tide returns to the saltmarsh.

Realigned saltmarshes are often lower than the local high tide level, and are rapidly filled with sediment and saltmarsh plants when the water returns. This creates a habitat that can attract wetland birds and, since the sediment has organic carbon associated with it, also generates and opportunity to bury carbon in the marsh.

This paper investigates two things: how much organic carbon was buried on a realigned saltmarsh in the first years after it was created, and how does this carbon burial compare to the emissions generated by the construction of the site.

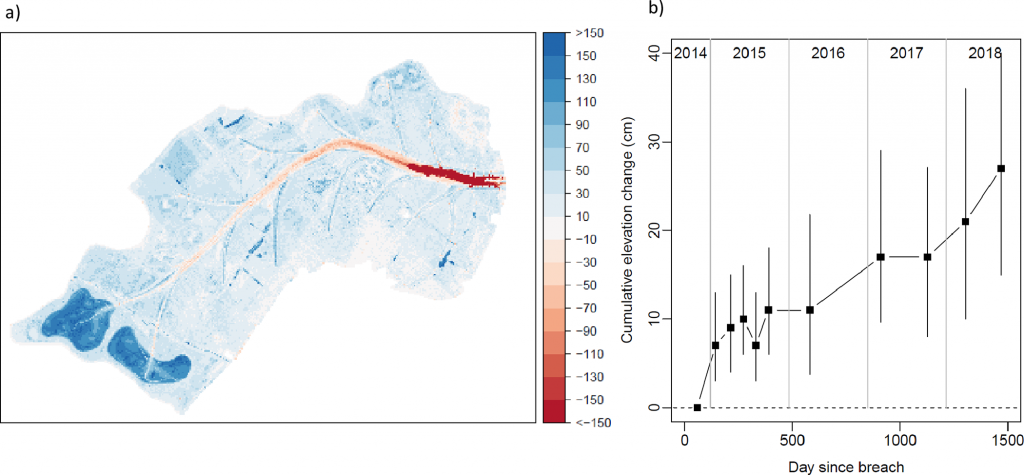

Samples were collected from Steart Marshes, a site in Somerset, UK, that was flooded in 2014. The samples were analysed for their total carbon and organic carbon content using analytical facilities here at Manchester Met. The carbon concentrations were scaled up to the entire site using sedimentation data calculated from laser scans of the marsh collected at different time points.

We found that the organic carbon burial rate (19 tonnes per hectare per year) was very high compared to other saltmarsh sites, mostly because the sediment built up very rapidly (75 mm per year) after the sea defences were breached. The organic carbon buried on site is much greater than the carbon emissions generated by the diggers and bulldozers used to make the new marsh, and so it seems that there has been a net climate benefit by creating the marsh.

However, the next piece of the puzzle is to fully understand the types of organic carbon being buried on the site. Not all carbon has the same climate benefit associated with it, and so further work is required to properly calculate the climate change mitigation potential of restoring saltmarshes.

Characterization of diverse bacteriohopanepolyols in a permanently stratified, hyper-euxinic lake

This paper is available Open Access via the journal website.

This publication, led by Molly O’Beirne from the University of Pittsburgh is a really exciting look at BHP biomarkers and microbes in an unusual Canadian lake. My role was to measure and identify the BHPs present in the lake, including finding a ‘new’ BHP that had not been described before.

Mahoney Lake, British Columbia, is a small lake with a really high concentration of sulfur, and a low concentration of oxygen. This classifies it as ‘euxinic‘, and Mahoney Lake is 100 times more sulfidic than the Black Sea. Not only that, but the lake switches from oxic to euxinic within the top 7-8 metres, meaning that sunlight can penetrate into the euxinic layer. This study looked at the changing bacterial communities and BHP biomarkers present in the different layers of the lake.

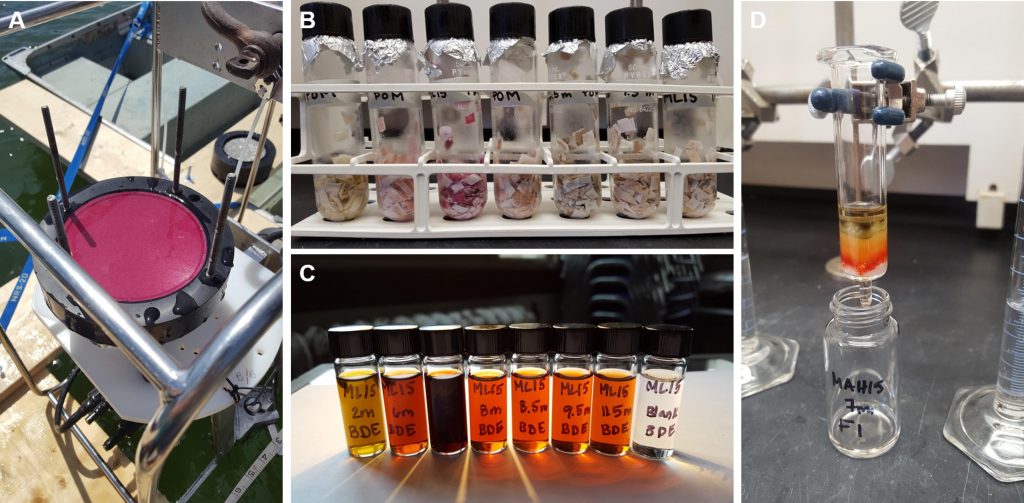

Water filter samples were collected at a series of depths in the lake, from the oxic layer, through the changeover to euxinia (the ‘chemocline’), down to the sediment at the bottom. At the chemocline, a large community of purple sulfur bacteria were collected which made the filters turn a bright pink-purple colour (see the picture above), which makes a nice change from the usual brown-grey water filters usually collected from lakes and rivers.

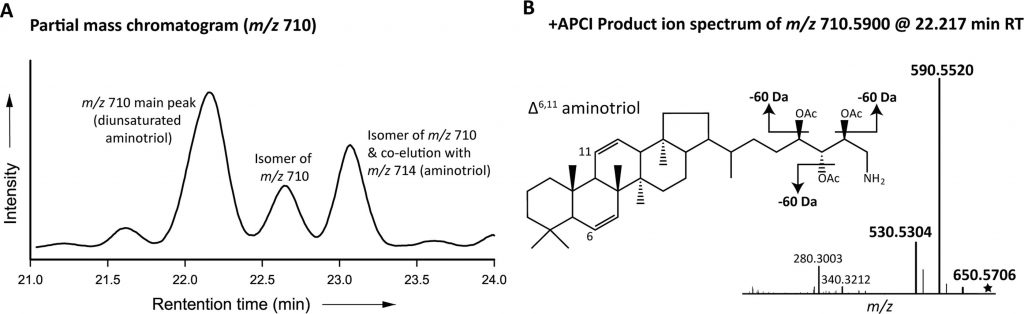

Back in the lab in Pittsburgh, these filters were extracted using solvents and the BHP molecules were separated out from everything else, transferred into small vials, and posted across the Atlantic. After a few days in customs, they made it to Manchester Metropoltian to be analysed on the LC-MS. When looking through the data, there were several common BHPs present, but also a large amount of a previously unknown BHP molecule. It was seen on the chromatogram at a similar time to the ubiquitous ‘aminotriol’ BHP, but careful analysis of the mass spectrum showed that the molecule and its fragments were four mass units ligher than aminotriol, with m/z (mass to charge ratio) 710 rather than 714. We think that this molecule has the same structure as aminotriol, but has two carbon-carbon double bonds in the structure.

Since this molecule was only found in the lower parts of the lake, we think it could be directly linked to euxinic environments. In future work, I will look for this molecule in other euxinic and oxic lake samples to test whether it is a reliable biomarker for euxnia. If it is, BHP 710 can be used to identify euxinia in ancient lakes throughout the geological record.

To find out which bacteria might be making these molecules, Trinity Hamilton from the University of Minnesota sequenced the bacterial genomes present in the lake filters. Genes that produce BHPs were found in samples from the lower parts of the lake, and the BHP producing bacteria are probably Deltaproteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetia, and Verrucomicrobia.

At the bottom of the lake, the BHPs present change again. Bacteriohopanetetrol (BHT) is the most common, and methylated BHTs are only found in the lake sediments. This makes us think that bacteria living in the oxygen-free sediments at the bottom of the lake are the source of the methylated BHTs, rather than bacteria living in the oxygenated upper layer of the lake.

Overall, this has been a really fun and interesting study to be part of, and provides loads of new research questions as well as answers. Other researchers looking to analyse BHPs in their samples are welcome to get in touch to discuss collaborations.