This paper is available Open Access via the journal website.

This publication, led by Molly O’Beirne from the University of Pittsburgh is a really exciting look at BHP biomarkers and microbes in an unusual Canadian lake. My role was to measure and identify the BHPs present in the lake, including finding a ‘new’ BHP that had not been described before.

Mahoney Lake, British Columbia, is a small lake with a really high concentration of sulfur, and a low concentration of oxygen. This classifies it as ‘euxinic‘, and Mahoney Lake is 100 times more sulfidic than the Black Sea. Not only that, but the lake switches from oxic to euxinic within the top 7-8 metres, meaning that sunlight can penetrate into the euxinic layer. This study looked at the changing bacterial communities and BHP biomarkers present in the different layers of the lake.

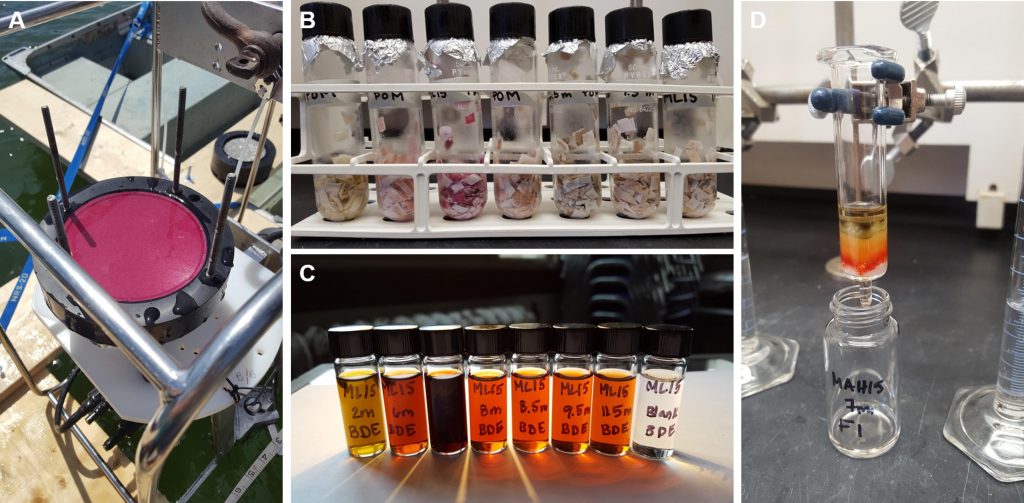

Water filter samples were collected at a series of depths in the lake, from the oxic layer, through the changeover to euxinia (the ‘chemocline’), down to the sediment at the bottom. At the chemocline, a large community of purple sulfur bacteria were collected which made the filters turn a bright pink-purple colour (see the picture above), which makes a nice change from the usual brown-grey water filters usually collected from lakes and rivers.

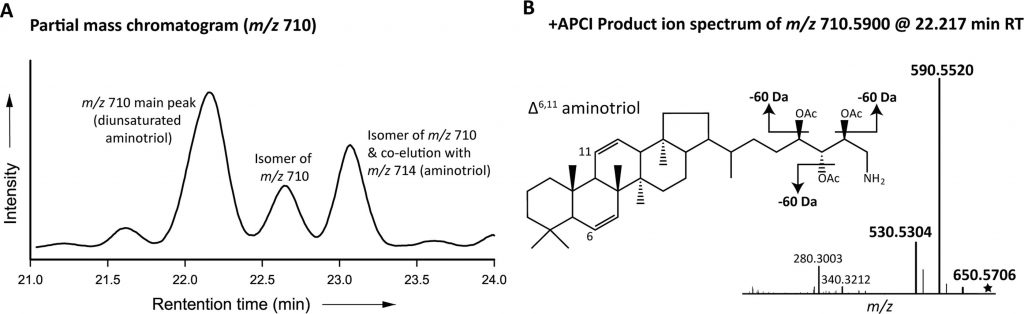

Back in the lab in Pittsburgh, these filters were extracted using solvents and the BHP molecules were separated out from everything else, transferred into small vials, and posted across the Atlantic. After a few days in customs, they made it to Manchester Metropoltian to be analysed on the LC-MS. When looking through the data, there were several common BHPs present, but also a large amount of a previously unknown BHP molecule. It was seen on the chromatogram at a similar time to the ubiquitous ‘aminotriol’ BHP, but careful analysis of the mass spectrum showed that the molecule and its fragments were four mass units ligher than aminotriol, with m/z (mass to charge ratio) 710 rather than 714. We think that this molecule has the same structure as aminotriol, but has two carbon-carbon double bonds in the structure.

Since this molecule was only found in the lower parts of the lake, we think it could be directly linked to euxinic environments. In future work, I will look for this molecule in other euxinic and oxic lake samples to test whether it is a reliable biomarker for euxnia. If it is, BHP 710 can be used to identify euxinia in ancient lakes throughout the geological record.

To find out which bacteria might be making these molecules, Trinity Hamilton from the University of Minnesota sequenced the bacterial genomes present in the lake filters. Genes that produce BHPs were found in samples from the lower parts of the lake, and the BHP producing bacteria are probably Deltaproteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetia, and Verrucomicrobia.

At the bottom of the lake, the BHPs present change again. Bacteriohopanetetrol (BHT) is the most common, and methylated BHTs are only found in the lake sediments. This makes us think that bacteria living in the oxygen-free sediments at the bottom of the lake are the source of the methylated BHTs, rather than bacteria living in the oxygenated upper layer of the lake.

Overall, this has been a really fun and interesting study to be part of, and provides loads of new research questions as well as answers. Other researchers looking to analyse BHPs in their samples are welcome to get in touch to discuss collaborations.